Polymorph Polyring P2P Topology

- Polymorph Tutorials

- Polymorph History

- Polymorph vs. Chord, Kademlia, Tapestry and Pastry

- Polymorph Polyring GUID Scheme

- Polymorph Polyring Message Routing

- Polymorph Polyring Routing Algorithm

- Polymorph Polyring Routing Table

- Routing Logic in Constant Time

- Flexible Scalability

- Topology Shaping

- Predictable Routing

- Broadcast and Multicast

- Content Caching

- Routing Table Management

- Hosted Peers vs. Autonomous Peers

- Single Point of Failure

- Congestion Points

- Peer Clusters

- Side Polyrings

- DOS Protection

- Privacy Protection

- Load Balancing

- Public and Private Peers

- Polymorph P2P Network Algorithm Summary

Jakob Jenkov |

The Polymorph Polyring P2P network topology is part of my Polymorph project which will be able to implement many different kinds of network topologies (polymorphic topology - topological polymorphism) - among others P2P network topologies. In this Polymorph P2P tutorial I will primarily be looking at the Polymorph polyring topology that can be used for P2P networks.

Polymorph Tutorials

You can read more about the Polymorph project in my tutorial series on Polymorph here:

Polymorph History

I started development of the Polymorph project in Q1 2021. The Polymorph P2P algorithm was first published July 30th 2021. Thus, Polymorph is a newer type of P2P network topology and thus looks different than the classic P2P algorithms.

Polymorph vs. Chord, Kademlia, Tapestry and Pastry

The main difference between Polymorph and Chord, Kademlia, Tapestry and Pastry is that polymorph uses a polyring topology whereas the other systems use a uniring topology. Both of these topologies are explained in the following sections.

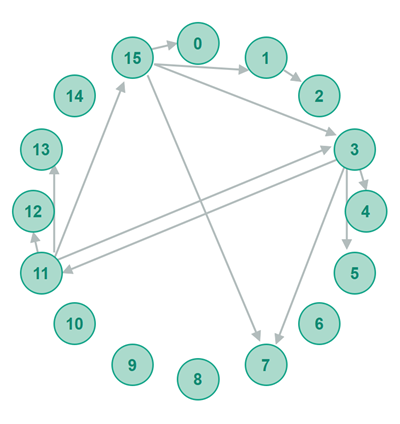

Uniring Topology

Chord, Kademlia, Tapestry and Pastry all use a uniring topology - a single, uniform ring topology. All peers in a Chord, Kademlia, Tapestry or Pastry network are part of the same ring. The diagram below shows a Chord uniring - but a Kademlia, Tapestry or Pastry uniring would only have differed in the connections between the peers - not in the uniform uniring topology itself. Here is how a uniring topology looks:

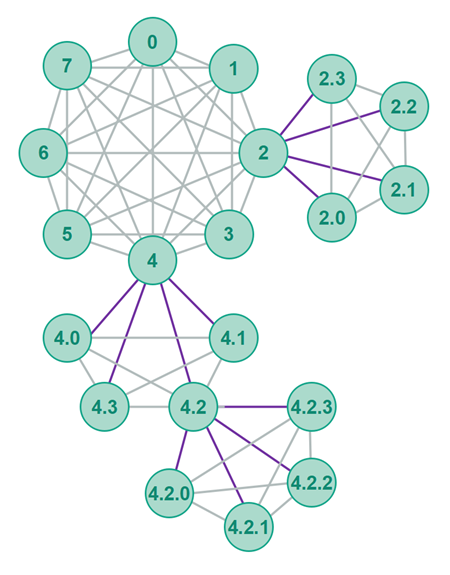

Polyring Topology

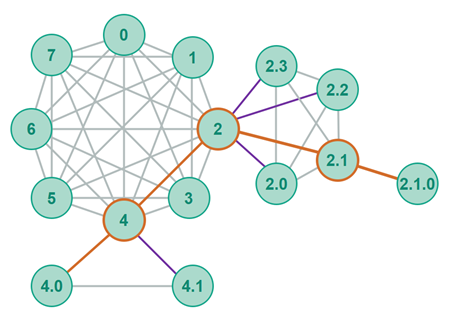

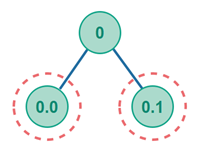

Polymorph P2P topology uses a polyring topology - multiple rings connected as a graph of rings - a ring graph. Here is an illustration of the Polymorph polyring topology:

The peers in a Polymorph polyring are organized into rings. All peers in a ring knows about all other peers in that ring. Thus, each ring can also be referred to as a mesh.

Around each peer a new, child ring can be formed. All peers in a child ring know each other. All peers in a child ring also knows its parent peer - and the parent peer knows all of the peers in its child ring. Thus, each peer knows:

- Its parent peer

- Its sibling peers

- Its child peers

The knowledge of child peers is only 1 level deep. Thus, a peer does not know any peers from the grandchild level and down. A peer only knows 1 level up, the same level (ring) as itself, and 1 level down in the polyring.

Polymorph Polyring GUID Scheme

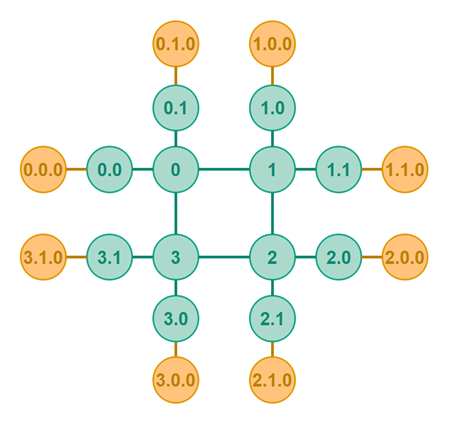

The Polymorph polyring uses dynamically sized GUIDs meaning the peers in a Polymorph polyring do not all have the same size GUID.

A Polymorph polyring GUID consists of one or more coordinates. Here are a few GUID examples:

[1] [1.0] [4.10.34.9875.2344]

The GUID coordinates of a peer depends on where in the polyring the peer is located.

The peers in the central ring in the polyring are given a single-coordinate GUID. This coordinate runs from 0 to infinity. For instance [0], [99], [1234] etc.

The peers in a child ring are given a GUID that has one coordinate more than the GUID of the parent ring. A child peer GUID starts with the full parent peer GUID and ends with the extra coordinate that makes the child GUID unique. Here is an example parent peer GUID with corresponding child peer GUIDs:

[3] : Parent peer GUID [3.0] : Child 0 peer GUID [3.1] : Child 1 peer GUID [3.2] : Child 2 peer GUID

This GUID scheme means that only the last coordinate differ between GUIDs of peers within the same child ring.

This last coordinate of any GUID can also go from 0 to infinity. Thus, peers in the child ring of peer [1] will get GUIDs from [1.0] to [1.infinity] . Peers in the child ring of peer [4.99.658] will get GUIDs from [4.99.658.0] to [4.99.658.infinity] .

Polymorph Polyring Message Routing

The Polymorph polyring topology is designed explicitly for message routing. That means, that peers do not lookup the IP address + TCP / UDP port number of the peers they want to communicate with. Instead, the sending peer forwards the message to the polyring which routes the message to the destination peer.

Message Routing Over TCP

For the message routing to be efficient over TCP, all peers in a Polymorph polyring keeps open TCP connections to all the peers it knows. That means, an open TCP connection to:

- Its parent peer

- Its sibling peers

- Its child peers

It takes time to complete a TCP handshake to open a new TCP connection. Therefore it is faster to keep open connections to all relevant peers through which the messages can be routed.

Additionally, it can take some time before a TCP connection gets up to its maximum speed. A TCP connection starts out sending data at a default speed, and then tries to increase the speed until it is no longer able to increase the speed (when IP packets start to get dropped).

Because of the TCP handshake and gradual transfer speedup - you will get a better performance when routing messages over already open TCP connections.

Polymorph Polyring Routing Algorithm

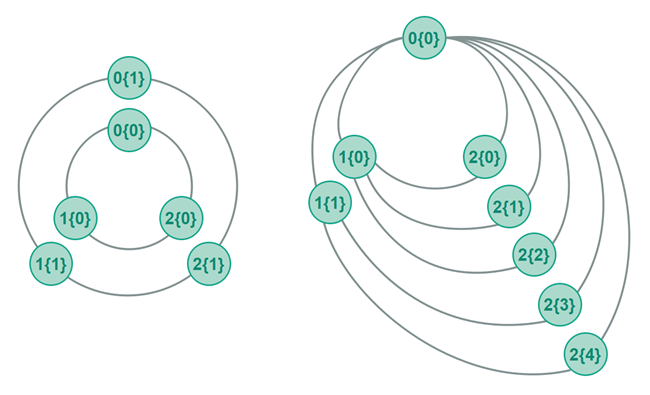

The Polymorph polyring routing algorithm is actually pretty simple. Any given peer can only forward a message to its parent, a sibling or a child. In other words, it can only forward the message to peers it already has an open connection to (if routing via TCP). This is illustrated in the diagram below, where the peer with GUID [4.2] (in yellow color) can route messages to either its parent, sibling or child peers.

Before I explain the routing algorithm I need to make a few definitions:

R = Routing peer D = Destination peer LR = Length of Routing peer's GUID in coordinates (coordinate count) LD = Length of Destination peer's GUID in coordinates (coordinate count)

First, the routing peer counts how many matching coordinates its own GUID has with the destination GUID, from left to right, until the first non-matching coordinate. I will refer to this number as M in the following sections.

M = Number of Matching coordinates between

routing peer's GUID and

destination peer's GUID,

from left to right,

until first non-matching coordinate.

Note that M cannot be larger than LR since M is calculated by counting matching coordinates of LR with LD. Thus, there can be maximally LR matching coordinates.

Here is an example of a coordinate match count:

Routing peer GUID: [4.7.8.87] Destination peer GUID: [4.7.3.87] M = 2

The routing peers GUID is [4.7.8.87] and the destination peer's GUID is [4.7.3.87]. The first 2 coordinates of these GUIDs match. The 3rd coordinates do not match. The 4th coordinate matches too, but that is irrelevant since the 3rd coordinates do not match. Thus, M is 2.

Once you know M, the rest of the routing algorithm is pretty straightforward. The routing algorithm is summarized here:

M <= LR - 2 => Not same parent. Route to parent.

M == LR - 1 && LD == LR - 1 => Destination is parent. Route to parent.

M == LR - 1 && LD >= LR => Destination is sibling or sibling descendant.

Route to sibling.

M == LR && LD == LR => Destination is self. Process message.

M == LR && LD > LR => Destination is descendant. Route to child.

The first check determines whether the destination peer is even within the same branch of the polyring as the routing peer. If the destination peer does not even have the same parent peer as the routing peer, then the destination peer is located in another branch of the polyring. The message must then be routed to the routing peer's parent - which will then forward it further until the message reaches its destination. Here are some examples of a routing peer and destination peers that do not share the same parent.

[2.3.4.50] : Routing peer GUID [2.3.8.10] : Destination peer GUID (M = 2, LR = 4) [1.3.4.50] : Destination peer GUID (M = 0, LR = 4)

The second check determines if the destination peer is the routing peer's parent peer itself. If it is, just route the message to its parent peer. Here is an example of this situation:

[2.3.4.50] : Routing peer GUID [2.3.4] : Destination peer GUID (M = 3, LR -1 = 3, LD = 3)

The third check determines if the destination peer is a sibling or sibling descendant of the routing peer. That is the case if the destination GUID has the same parent peer, but a different coordinate than the last coordinate of the routing peer. The message must then be routed to the corresponding sibling. Here are some examples of this case:

[2.3.4.50] : Routing peer GUID [2.3.4.51] : Destination peer GUID (sibling) (M = 3, LR - 1 = 3, LD = 4) [2.3.4.51.9] : Destination peer GUID (sibling descendant) (..., LD = 5) [2.3.4.51.9.2] : Destination peer GUID (sibling descendant) (..., LD = 6)

The fourth check determines if the message is for the routing peer itself. If it is, then the routing peer should just consume it (process it) itself. No further routing is required. Here is an example of this case:

[2.3.4.50] : Routing peer GUID [2.3.4.50] : Destination peer GUID (M = 4, LR = 4, LD = 4)

The fifth check determines if the message is for a child or descendant of the routing peer. If it is, the message should be routed to the corresponding child. Here are some examples of this case:

[2.3.4.50] : Routing peer GUID [2.3.4.50.1] : Destination peer GUID (child) (M = 4, LR = 4, LD = 5) [2.3.4.50.1.4] : Destination peer GUID (descendant) (M = 4, LR = 4, LD = 6)

Alternative Routing Algorithm Summaries

Another way to summarize the Polymorph polyring routing algorithm is:

M <= LR - 2 => Not same parent. Route to parent.

M == LR - 1

LD == LR - 1 => Destination is parent. Route to parent.

LD >= LR => Destination is sibling or sibling descendant.

Route to sibling.

M == LR

LR == LD => Destination is self. Process message

LR < LD => Destination is descendant. Route to child.

And yet another way to summarize the routing algorithm is:

Route to parent if

M <= LR - 2 => Not same parent. Route to parent.

M == LR - 1 &&

LD == LR - 1 => Destination is parent. Route to parent.

Route to sibling if

M == LR - 1 &&

LD >= LR => Destination is sibling or sibling descendant.

Route to sibling.

Route to child if

M == LR &&

LR < LD => Destination is descendant. Process message.

Route to self if

M == LR &&

LR == LD => Destination is self. Route to self.

Polymorph Polyring Routing Table

The routing table of a peer in a Polymorph polyring contains the following:

- The parent peer

- List of sibling peers

- List of child peers

If the list of sibling peers and child peers are implemented as array based lists (ArrayList in Java), then lookup into these lists can be made in constant time.

Sibling peers should be stored at the index in the list corresponding to the first coordinate that is different from the peer owning the routing table (the routing peer) - which is coordinate M + 1. For example:

[1.56.89] = Routing peer GUID

[1.56.45] = Sibling peer GUID.

M = 2. Index coordinate = 3.

Index in sibling list = 45

[1.56.11] = Sibling peer GUID.

M = 2. Index coord is 3rd coord.

Index in sibling list = 11

Similarly, child peers should be stored at the index in the list corresponding to the first coordinate that is different from the peer owning the routing table (the routing peer) - which is also coordinate M + 1. For example:

[1.56.89] = Routing peer GUID

[1.56.89.0] = Child peer GUID.

M = 3. Index cord is 4th coord.

Index in child list = 0

[1.56.89.23] = Child peer GUID.

M = 3. Index coord is 4th coord.

Index in child list = 23

Routing Logic in Constant Time

The routing algorithm and the routing table design explained in the earlier sections make it possible for a routing peer to make a routing decision in constant time - regardless of how many sibling and child peers it has references to.

A routing decision can be made with at most 4 comparisons (if-statements) and 1 array list lookup.

In comparison, the Chord, Kademlia, Pastry and Tapestry routing tables and algorithms require at least log(N) comparisons, or some variant of log(N) comparisons, to make a routing decision (as far as I understand) - where N is the number of entries in the routing table.

Flexible Scalability

The Polymorph polyring topology offer some interesting scalability options which I will discuss in the following sections.

2-Dimensional Scaling

The first thing to notice is, that the polyring can be scaled out along 2 dimensions:

- The number of peers in each ring can be increased.

- The depth level of rings can be increased.

The first dimension is the number of peers in a ring. This options means that you can add as many peers as you like within a single ring. A ring is never "full". Just keep in mind that as the number of peers in a ring goes up, so does the number of peers each peer needs to reference in its routing table. If TCP communication is used, the number of open TCP connections required for each peer also goes up when the number of peers its routing table goes up.

The second dimension is the number and levels of child rings. This option means that you can keep adding child rings to the polyring recursively. There is no upper limit on the number or levels of child rings. The polyring is never "full". Just keep in mind that as you increase the levels of child rings, the number of hubs needed to route a message from and to peers in the outer level rings increase.

This 2-dimensional scalability option means that you get more choice to scale up the polyring in a way that suits your concrete needs.

Fixed Hub Count Scalability

The ability to scale out by adding new peers to existing rings means that you can scale out a polyring while keeping the routing hub count fixed. Remember, the number of hubs required to route a message from one peer to another depends on the number of ring levels in the polyring.

Topology Shaping

The flexible extensibility and scalability of the Polymorph polyring makes it possible to shape the topology of the polyring more to your needs. This doesn't mean that the polyring topology is right for all distributed systems, but it can definitely be adapted better to more needs than a traditional P2P uniring.

The polyring can take on asymmetric topologies. This unlocks some interesting topology shaping options which I will cover in the following sections.

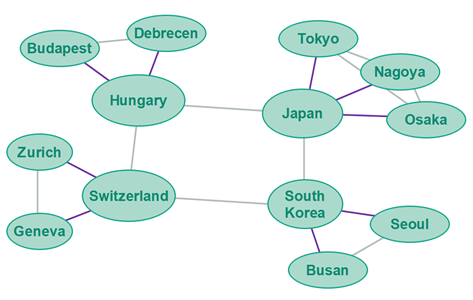

Geographically Aligned Topology

It is possible to shape the topology after the geographical location of the peers in the network. For instance, the peers in the center ring could be used to group child peers within different countries. Thus, all peers located in Japan would join a child ring of the Japan center ring peer. All peers in Brazil would join a child ring of the Brazil center ring peer etc.

Obviously, as the number of peers within a given country grows, you may need to divide them up into multiple layers of rings under the country root peer. Below is an example of a geographically aligned toplogy with country peers in the center ring and city peers in the first level child rings.

Geographical grouping of peers makes sense when peers located close to each other geographically are expected to communicate more with each other. Thus, more of the communication in the polyring will remain in the outer levels of the polyring.

Geographical grouping can also make sense if data exchanged between peers located in the same country is not allowed to be routed via foreign countries.

Traffic Aligned Topology

It is also possible to group peers according to which other peers the expect to be communicating with. The closer in the polyring a peer is located to the other peers it is communicating with, the less hubs are required to route messages between them, the faster the communication is, and the less load the communication puts on the polyring.

Predictable Routing

An interesting feature of the Polymorph polyring is that the routing between the peers in the polyring follows a predictable path through the polyring.

Predictable routing enables functionality such as broadcast, multicast and content caching along the routing paths etc. I will get into more detail about some of these features later in this tutorial.

Broadcast and Multicast

Because of the predictable routing feature of the polyring, it is possible to implement efficient broadcast and multicast within a polyring.

Broadcast

Broadcasting a message in a polyring means sending that message to all peers in the polyring. Because of the predictable routing of the polyring - broadcasting a message can be done efficiently. The sending peer does not need to know all peers in the polyring, nor does it need to send the message to all these peers individually. The polyring can replicate the message intelligently during propagation.

A peer that wants to broadcast a message within a polyring to all other peers in the entire polyring. will simple forward the message to all peers it knows in its routing table. That means following these steps:

- Send message to parent peer.

- Send message to all sibling peers.

- Send message to all child peers.

How a peer routes a broadcast message received from another peer, depends on whether the message is received from a child, a sibling or a parent peer. In other words, whether the message is currently being propagated up or down the routing peers branch of the polyring. Here are the steps:

- If the message came from a child peer:

- Route message to parent peer.

- Route message to all sibling peers.

- If the message came from a sibling peer:

- Route message to all child peers.

- If the message came from a parent peer:

- Send message to all child peers.

If a peer receives a broadcast message from a child peer, then that message is currently being routed up this branch of the polyring. The child peer only knows its parent peer upwards in the polyring, so the parent peer is responsible for routing the message to its siblings and its own parent. However, the other children of the receiving peer will be a sibling of the child it received the message from - so these peers will already have received the message directly from the child peer.

If a peer receives a broadcast message from a sibling peer, then that message is currently being routed sideways in the branch. All other siblings of the receiver are also siblings of the sender, and will already have received the message directly from the sender. Also, the receiver's parent peer is also the sending peer's parent, so the parent peer will already have received the message directly from the sending peer. Therefore, when receiving a broadcast message from a sibling it is only routed to the receiving peer's child peers.

If a peer receives a broadcast message from a parent peer, then that message is currently being routed down this branch of the polyring. The siblings of this child peer will already have received the message from the parent peer. Thus, the message is only routed down to its child peers.

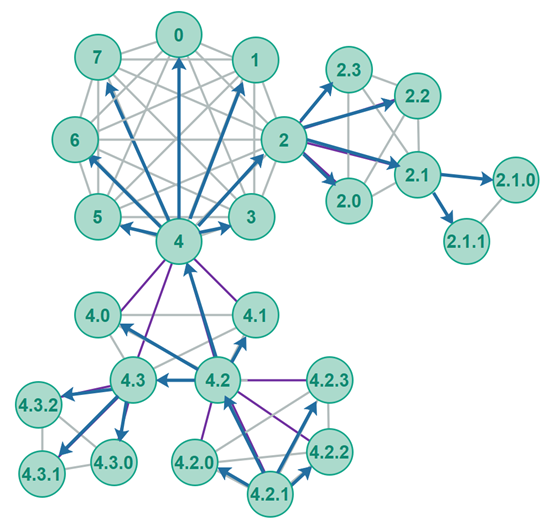

The diagram below illustrates a broadcast propagated in a Polymorph polyring P2P network. The broadcast starts from peer 4.2.1 . The blue arrows show the direction of the propagation of the broadcast. The diagram shows examples of both routing inwards to parent, sidewards to siblings and outwards to children.

Broadcast Optimization

To enable faster propagation of broadcast messages throughout the polyring I suspect it will be best to route a message inward (to parent) before routing it sideways (to siblings). In other words, when routing a message inward from a branch the propagation will parallelize better by first routing the message to its parent, and second to its siblings.

Routing inwards before sideways will enable the message to reach as many branches in the polyring as fast as possible. I suspect this will result in faster propagation throughout the polyring.

Routing sideways before inwards would result in the senders own branch being saturated before the message finally reached the center ring and gets propagated to the rest of the branches in the polyring. I suspect this will result in slower propagation throughout the polyring than if you first route up the branch before sideways.

Multicast

Multicast means sending the same message to multiple peers in the polyring, but not to all peers. When multicasting a message, the sending peer does need to know all the peers that is to receive the message.

Multicast follows the same algorithm as broadcast, except a routing peer needs to determine whether a message needs to be routed to its siblings, children or parent - depending on whether any of the receivers are a sibling, sibling descendant, child, descendant, parent, or located somewhere else in the polyring. There is no reason to forward a message unnecessarily to a part of the polyring which has no receivers of the message.

Additionally, a routing peer should probably only include the receivers in the routed message that are located within the section of the polyring the message is routed towards.

This means, that when routing a message up to a parent, no child, descendant, sibling or sibling descendant receivers need be included in the message. When routing a message sideways to a sibling, only the receiver GUIDs that is either the sibling itself, or a descendant of the sibling the message is routed to, should be included in the message. And when routing a message message down to a child, only the child GUID or descendant receiver GUIDs should be included in the message.

By targeting the receiver GUIDs included in the message to only those relevant for the peer the message is forwarded to, the messages are kept shorter, and each intermediate peer knows less about which other peers in the polyring has received the message.

The same propagation optimization applies to multicast as applies to broadcast: Routing messages up before sideways will probably result in faster propagation throughout the polyring.

By the way - a more efficient way of implementing multicast would be by having the subset of peers interested in the multicast join a side polyring and then broadcast to all the peers within that side polyring. Broadcast would not require including the GUIDs of the receivers, so for multicasts with many receivers - this would save a lot of GUID data in the broadbast messages.

Content Caching

The predictable routing feature enables a Polymorph polyring to cache content such as video, images, audio, text, scripts etc. throughout the polyring. When a file has been routed from a source peer to a destination peer, that content can be cached along the routing path. Later requests for the same file can possibly be served from a caching peer, provided the caching peer is on the routing path to the destination peer.

Exactly which caching scheme that is optimal depends on the exact traffic patterns of the peers in the polyring - which again depends on what the peers in the polyring are doing (the use case).

A simple caching scheme would be to cache content on the way from the source peer to the center ring. Since the route from the center ring to the source peer is the same for all peers in other branches of the polyring, all requests from these peers for the cached content can be served from these caching peers.

The diagram below shows the routing path (the orange lines) from the source peer [2.1.0] to the consuming peer [4.0]. The content could be cached efficiently anywhere along the orange path - especially within the branch of the source peer (from peer [2] and outward).

Routing Table Management

Routing table management in a Polymorph polyring is actually pretty simple.

When a peer joins a polyring it either joins the center ring, or the child ring of some parent ring.

If a peer joins the center ring - it will need to connect at least one of the other peers in the center ring. From the first peer the joining peer can get a list of all the sibling peers in the center ring. The joining peer then has a full routing table and can open connections to the other peers in the center ring.

If a peer joins a child ring of some parent peer, the joining peer connects to the parent peer to join its child ring. From the parent peer the the joining peer can get a full list of all child peers already in the ring. The existing child peers in the ring will be the siblings of the joining peer. The joining peer now has a full routing table and can open connections to the other peers in the child ring (its siblings).

Similarly, when a peer wants to leave a polyring - it already contains a full list of all the peers that need to know. The leaving peer can notify its parent, siblings and children that it is leaving. The notified parent and sibling peers can then remove the leaving peer from their routing table.

The leaving peer's children will have to rejoin the polyring somewhere else, and will get a new GUID. The grandchildren and other descendants of the leaving peer will also have to rejoin the network somewhere else and get a new GUID.

A leaving peer has a sizeable number of descendants will cause a lot of peers to have to rejoin the network in new locations. It is possible that with more research, a smarter leave protocol can be found which does not require descendant peers to have to rejoin. Perhaps only the children of the leaving peer need to rejoin, and the descendants can simply be assigned new GUIDs matching their new location. I will have to look into that.

Hosted Peers vs. Autonomous Peers

As mentioned in the article about Peer Connectivity, it can be useful for a developer of P2P network software to host a set of peers that can help boot the network from scratch. Joining autonomous peers can then connect to these hosted boot peers and via them find other autonomous peers in the network.

The polyring topology makes it easier to decide what part of the polyring to host. Typically the peers in the center ring will be hosted peers - and possibly also the peers in level 2 of the polyring - depending on the needs of the network provider.

The diagram below shows an example of a mixed polyring with the two inner levels being hosted peers (the green peers) and the outer level being autonomous peers (the yellow peers).

Single Point of Failure

Any peer in a Polymorph polyring is essentially a single point of failure for all its descendant peers. If a parent peer fails or leaves the polyring, all descendent peers also become detached from the polyring.

The closer to the center ring a given peer is located, the more descendant peers is at risk of being detached if the peer fails.

The single point of failure problem can be solved with peer clusters.

Congestion Points

If traffic is reasonably evenly distributed across a polyring, including across branches in the polyring, the center rings can become a point of congestion for traffic to and from the entire branch attached to that center peer.

Whether the center peers will actually become congestion points depends on the traffic patterns of the peers in the polyring. For instance, in a chat system where the peers are organized after geography, it can be assumed that most peers will communicate with peers that are geographically near themselves. Thus, most traffic will occur internally in each polyring branch, and not across branches.

Congestion point problems can be solved with peer clusters and with Side polyrings.

Peer Clusters

The first solution is peer clusters. Instead of having a branch of the polyring attached to only a single center peer, you can attach the branch to a cluster of peers.

A peer cluster is two or more peers that share the same GUID. All single-node peers (parent, siblings and children) must connect to all peers in a peer cluster. Thus, all peers in a peer cluster have the same connections to single-node peers.

If two peer clusters are connected to each other, for instance two peer clusters in the center ring, then the peers in the cluster distribute the connections to the peers in the other cluster among themselves. Thus, the peers in a peer cluster do not all have the same connections to peers in another peer cluster. This peer cluster to peer cluster connection distribution is done to keep the number of connections for each peer down.

The diagram below shows two polyrings with peer clusters. The left polyring has symmetric clustering. As you can see, with symmetric clustering the two center rings are disconnected. Once a child of any of the center peers route a message to one of the center peers, that message will stay within the cluster ring it enter the center ring on. In the polyring using asymmetric clustering you can see that the cluster peers are not all connected to each other. The nodes in peer cluster 2 divide the connections to the nodes in peer cluster 1 among them - as evenly as they can.

When routing traffic to a peer cluster, the routing peer chooses to route the message to only one of the peers in the cluster. This makes sure that traffic is balanced out over the peers in the peer cluster. This load balancing results in less congestion around that peer cluster.

If one peer in a peer cluster leaves or fails, the rest of the peers in the peer cluster can keep the branch alive and attached to the polyring. No child peers need change their GUIDs or rejoin the polyring.

It is theoretically possible to scale out peer clusters indefinitely. In practice you will probably have to experiment with what number of peers in a peer cluster makes sense. This depends on traffic patterns and leave / failure patterns of the peers in the cluster.

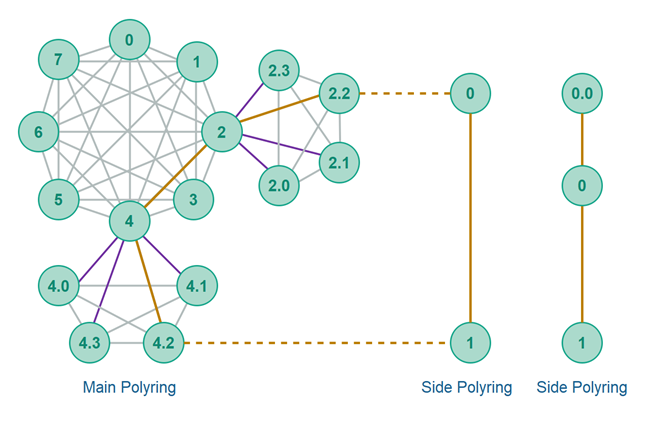

Side Polyrings

Side polyrings (AKA side fabrics, side rings or side networks) are a solution to the traffic congestion point problem.

Imagine a user (peer) finds a service (another peer) in a Polymorph polyring that it wants to use heavily. For instance, the user wants to watch some videos stored at the service peer. To watch these videos, the user must download these videos from the service peer. To download the videos they must be routed via the polyring from the service peer to the user peer. This puts heavy load on the polyring. If many users have similar traffic patterns, this can heavily congest the polyring - especially if the traffic needs to be loaded over the center peers.

Instead of routing heavy traffic via the main polyring, a service peer can provide a side polyring through which the heavy traffic can be routed. A side polyring is just another polyring that is separate from the main polyring. This side polyring is reserved for the service peer's users. The user and service peers can use the main polyring for discovery of peers and content, and the side polyrings for the heavy communication.

A reserved side polyring will most likely be smaller ring-level wise, and thus offer fewer hubs when routing messages over it. Thus, a side polyring will most likely be faster than routing heavy traffic via the main polyring.

Additionally, since the side polyring only routes content offered by a single (or a few) services, there will be less traffic routed through it than what would be routed through the main polyring if all traffic was to be routed through the main polyring. This lower traffic amount again helps lower congestion and increase performance of the side polyring.

The diagram below shows a main polyring with two possible side ring topologies. Imagine peer [2.2] is offering some service that peer [4.2] wants to use. Instead of using it directly via the main polyring, peer [2.2] may offer a side ring specifically for making its service available with better performance. The diagram shows two such possible side ring topologies: A direct connection between the peers, and a topology with a single peer in between.

DOS Protection

If client peers communicate with service peers via a polyring (whether main or side polyring), then the client does not know the exact IP address of the service peer. Only the polyring knows that. This makes it harder to launch DOS (Denial of Service) attacks against a given service. If a polyring experiences heavy load, it can be scaled out to match the load (theoretically, at least). Congestions points can be clustered and scaled out too. High traffic client peers can be rate limited or denied access to the polyring. Well-known client peers can be given preferred access points to the polyring etc. etc.

Privacy Protection

Since peers at the edge of a polyring are not directly connected to each other, it is not immediately visible which peers are communicating with each other just by looking at the network connections themselves. You would need to inspect the exchanged messages themselves which contain the the sender and receiver GUIDs. The messages could be protected with encryption, though, and probably should be to mitigate the risk of hackers sniffing the messages.

Load Balancing

It is possible to have a parent peer load balance messages among child peers (if you programmed it to do so). This is possible due to the predictable routing of a Polymorph polyring.

Public and Private Peers

If some of the edge peers in a Polymorph polyring are private, meaning they are behind a firewall or NAT, then its siblings cannot connect directly to it. Its siblings must then communicate with it via their shared parent peer. Exactly how this is supposed to be implemented is still not fully explored - but it should be possible to implement. The challenge is for a sibling to know when to try to communicate directly with a peer, or try to go via their shared parent peer.

One solution could be to have the GUID itself could contain information about whether a given peer is public or private.

Another solution could be to have the parent peer tell all its children about private peers, so siblings can mark that in their reference to the private peer in their routing table.

The diagram below shows two private peers that have to communicate via a parent peer, because they cannot connect to each other directly.

Polymorph P2P Network Algorithm Summary

As you can see, the Polymorph P2P network algorithm has a lot of different use cases - and probably even some not mentioned above. Many different types of services could be layered on top of a Polymorph polyring.

One use case I am currently looking into is how to layer a Distributed Hashtable (DHT) on top of a polyring - and whether that even makes sense - or if a DHT would benefit more from a slightly more tailored topology.

Another use case is pub-sub type functionality - which is possibly just a variant of multicast.

| Tweet | |

Jakob Jenkov | |