Caching Techniques

Jakob Jenkov |

Caching

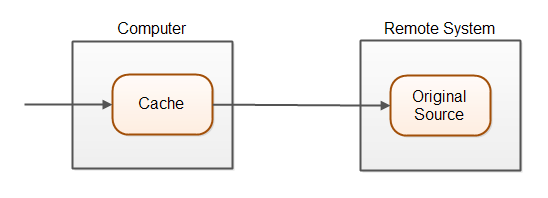

Caching is a technique to speed up data lookups (data reading). Instead of reading the data directly from it source, which could be a database or another remote system, the data is read directly from a cache on the computer that needs the data. Here is an illustration of the caching principle:

A cache is a storage area that is closer to the entity needing it than the original source. Accessing this cache is typically faster than accessing the data from its original source. A cache is typically stored in memory or on disk. A memory cache is normally faster to read from than a disk cache, but a memory cache typically does not survive system restarts.

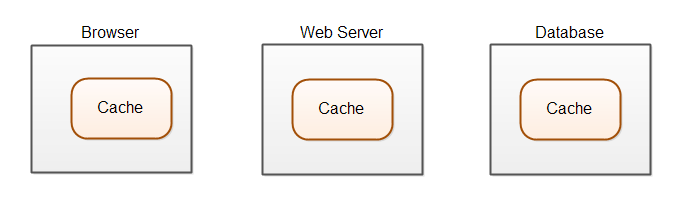

Caching of data may occur at many different levels (computers) in a software system. In a modern web application caching may take place in at least 3 locations, as illustrated below:

Most modern web applications use some kind of database. The database may cache data in memory so it does not have to read it from disk. The web server may cache static files like images, CSS files, JavaScript etc. in memory instead of reading that from disk every time they are needed. The web application may cache data read from the database, so it does not have to access that in the database (via the network) every time it is needed. And finally the browser may cache static files and data too. In HTML5 browsers have local storage, an application cache, and a web SQL database in which they can store data.

When implementing a cache you have the following three issues to think about:

- Populating the cache

- Keeping the cache and remote system in sync

- Managing cache size

I will get into these three issues throughout the rest of this text.

Populating the Cache

The first challenge of caching is to populate the cache with data from the remote system. There are basically two techniques to do this:

- Upfront population

- Lazy population

Upfront population means that you populate the cache with all needed values when the system keeping the cache is starting up. Being able to do so requires that you know what data to populate the cache with. You may not always know what data should be inserted into the cache at system startup time.

Lazy evaluation means that you populate the cache the first time a certain piece of data is needed. First you check the cache to see if the data is already there. If not, you read the data from the remote system and insert into the cache.

I have summed up the advantages and disadvantages of upfront and lazy population in the table below:

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Upfront population | Upfront population has no one-off cache read delays like lazy population has. | The initial build of the cache make take a long time. You risk caching data that is never read. |

| Lazy population | Lazy population only caches data that is actually read. Lazy population has no upfront cache build delay. |

Lazy population of the cache will not have any speedup from the first cache read, since this is the time the data is fetched from the remote system and inserted into the cache. This may result in an inconsistent user experience. |

Of course it is possible to combine upfront and lazy population. Perhaps you populate the cache with the most read data upfront, and let the rest of the data be populated lazily.

Keeping Cache and Remote System in Sync

A big challenge of caching is to keep the data stored in the cache and the data stored in the remote system in sync, meaning that the data is the same. Depending on how your system is structured, there are different ways of keeping the data in sync. I will cover some of the possible techniques in the following sections.

Write-through Caching

A write-through cache is a cache which allows both reading and writing to it. If the computer keeping the cache writes new data to the cache, that data is also written to the remote system. That is why it is called a "write-through" cache. The writes are written through to the remote system.

Write-through caching works if the remote system can only be updated via the computer keeping the cache. If all data writes goes through the computer with the cache, it is easy to forward the writes to the remote system and update the cache correspondingly.

Time Based Expiry

If the remote system can be updated independently of the computer keeping the cache, then it can be a problem to keep the cache and the remote system in sync.

One way to keep the data in sync is to let the data in the cache expire after a certain time interval. When the data has expired it will be removed from the cache. When the data is needed again, a fresh version of the data is read from the remote system and inserted into the cache.

How long the expiration time should be depends on your needs. Some types of data (like an article) may not need to be fully up-to-date at all times. Maybe you can live with a 1 hour expiration time. For some articles you might even be able to live with a 24 hour expiration time.

Keep in mind that a short expiration time will result in more reads from the remote system, thus reducing the benefit of the cache.

Active Expiry

An alternative to time based expiration is active expiration. By active expiration I mean that you actively expire the cached data. For instance, if your remote system is updated you may send a message to the computer keeping the cache, instructing it to expire the data that was updated.

Active expiry has the advantage that the data in the cache is made up-to-date as fast as possible after the update in the remote system. Additionally, you don't have any unnecessary expirations for data that has not changed, as you may have with time based expiration.

The disadvantage of active expiration is that you need to be able to detect changes to the remote system. If your remote system is a relational database, and this database can be updated through different mechanisms, each of these mechanisms need to be able to report what data they have updated. Otherwise you cannot send an expiration message to the computer keeping the cache.

Managing Cache Size

Managing cache size is an important aspect of caching too. Many system has so much data stored that it is impossible, or unfeasible, to store all of that data in the cache. Therefore you need a mechanism to manage how much data you store in the cache. Managing the cache size is typically done by evicting data from the cache, to make space for new data. There are a few standard cache eviction techniques. These are:

- Time based eviction.

- First in, first out (FIFO).

- First in, last out (FILO).

- Least accessed.

- Least time between access.

Time based eviction is similar to time based expiration which has been covered earlier. In addition to keeping the cache in sync with the remote system, time based expiration can also be used to keep the cache size down. Either you have a separate thread running which monitors the cache, or the clean up is done when attempting to read or write a new value to the cache.

First in, first out means that when you attempt to insert a new value into the cache, you remove the earliest inserted value to make space for the new one. Of course you do not remove any values before the cache meets its space limit.

First in, last out is the reverse of the FIFO method. This method is useful if the first stored values are also the ones that are typically accessed the most.

Least accessed eviction means that the cache values that have been accessed the least number of times are evicted first. The purpose of this technique is to avoid having re-read and store often read values. In order to make this technique work, the cache has to keep track of how many times a given value has been accessed.

An issue to keep in mind using least accessed eviction is that old values in the cache automatically has a higher number of accesses, even if they are not accessed anymore. Perhaps an old article has been accessed a lot in the past, but is now being accessed a lot less. The article's access count is still high though, meaning it does not get evicted despite lower access counts now. To avoid this situation, the access count could count accesses within the last N hours. But this further complicates the access counting.

Least time between access eviction takes the time between accesses of a value into account. When a value is accessed the cache marks the time the value was accessed and increases the access count. When the value is accessed the next time, the cache increments the access count, and calculates the average time between all accesses. Values that were once accessed a lot but fade in popularity will have a dropping average time between accesses. Sooner or later the average may drop low enough that the value will be evicted.

A variation of the least time between access eviction is to only calculate the time for the last N accesses. N could be 100, 1.000 or some other number that makes sense in your application. Whenever the access count reaches N, the access count is reset to 0 and the time of the access is stored too. This approach will evict values with fading popularity faster than if the total access count and time was used.

Another variation of least time between access is to reset the access count at regular intervals, and just use least accessed eviction. For instance, for every hour a value is cached, the access count for the previous hour is stored in another variable for use in eviction decisions. The access count for the next hour is reset to 0. This mechanism will have the same effect as the variation described above.

The difference between the last two variations comes down to checking if the

access count has reached N, or if the time interval has exceeded Y, for every

cache access. Since checking an integer is typically faster than

reading the system clock, I would go with the first approach. The first approach

only reads the system clock every N accesses, whereas the second approach reads

the system clock for every access (to see if the time interval has expired).

Remember, that even if you are using cache size management, you may still have to evict, read and store values in order to make sure they are in sync with the remote system. Even if a cached value is accessed a lot and thus deserves to stay in the cache, sometimes it may need to be synchronized with the remote system.

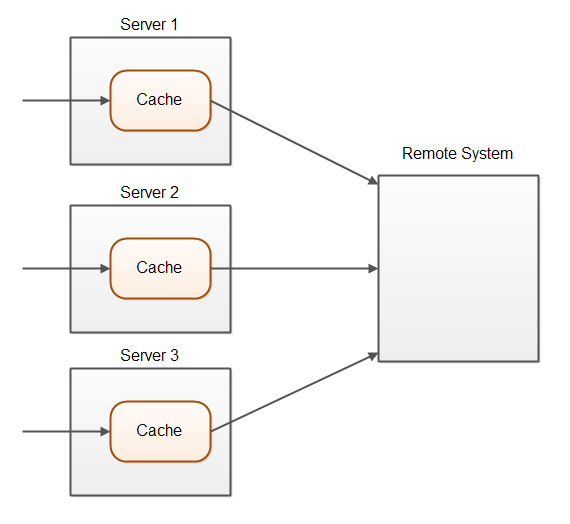

Caching in Server Clusters

Caching is simpler in systems that runs on a single server. With a single server you can assure that all writes go through the same server and thus use a write-through cache. The situation is more complicate when your application is distributed across a cluster of servers. The following diagram illustrates this situation:

A simple write-through cache will only update the cache on the server that executes the write operation. The cache on the other servers will know nothing of that write operation.

In a server cluster you may have to either use time based expiration or active expiration to make sure that all caches are in sync with the remote system.

Cache Products

Implementing your own cache is not too hard, depending on how advanced you need it to be. However, if you are not in the mood to implement your own cache, there exist many different ready-to-use caching products. Some of these products are:

I do not know these products well enough to make a recommendation, but I know what both are in widespread use.

| Tweet | |

Jakob Jenkov | |