Compare and Swap

Jakob Jenkov |

Compare and swap is a technique used when designing concurrent algorithms. Basically, compare and swap compares the value of a variable with an expected value, and if the values are equal then swaps the value of the variable for a new value. Compare and swap may sound a bit complicated but it is actually reasonably simple once you understand it, so let me elaborate a bit further on the topic.

By the way, compare and swap is sometimes abbreviated CAS, so if you see some articles or videos about concurrency mention CAS, there is a good chance that it refers to compare and swap operations.

Compare and Swap Tutorial Video

If you prefer video, I have a video version of this compare and swap tutorial here:

Compare and Swap Tutorial Video

Compare and Swap for Check Then Act Cases

A commonly occurring pattern in concurrent algorithms is the check then act pattern. The check then act pattern occurs when the code first checks the value of a variable and then acts based on that value. Here is a simple example:

public class ProblematicLock {

private volatile boolean locked = false;

public void lock() {

while(this.locked) {

// busy wait - until this.locked == false

}

this.locked = true;

}

public void unlock() {

this.locked = false;

}

}

This code is not a 100% correct implementation of a multi-threaded lock. That is why I have named it

ProblematicLock. However, I have created this faulty implementation to illustrate how

its problems can be fixed via compare and swap functionality.

The lock() method first checks if the locked member variable is equal

to false. That is done inside while-loop. If the locked variable

is false, the lock() method leaves the while-loop and

sets locked to true. In other words, the

lock() method first checks the value of the locked variable, and

then acts based on that check. Check, then act.

If multiple threads had access to the same ProblematicLock instance, the above lock() method

would not be guaranteed to work. For example:

If thread A checks the value of locked and sees that it is false (expected value),

it will exit the while-loop to act upon that check. If thread B also checks the

value of locked before thread A sets the value of locked to true,

then thread B will also exit the while-loop to act upon that check.

This is a classical race condition.

Check Then Act - Must Be Atomic

To work properly in a multithreaded application (to avoid race conditions), check then act operations must be atomic. By atomic is meant that both the check and act actions are executed as an atomic (non-dividable) block of code. Any thread that starts executing the block will finish executing the block without interference from other threads. No other threads can execute the atomic block at the same time.

A simple way to make a block of Java code atomic is to mark it using the synchronized Java keyword.

See my Java synchronized tutorial for more details.

Here is the ProblematicLock from earlier with the lock() method turned into an atomic block of code

using the synchronized keyword:

public class ProblematicLock {

private volatile boolean locked = false;

public synchronized void lock() {

while(this.locked) {

// busy wait - until this.locked == false

}

this.locked = true;

}

public void unlock() {

this.locked = false;

}

}

Now the lock() method is synchronized so only one thread can executed it at a time on the same

MyLock instance. The lock() method is effectively atomic.

Blocking Threads is Expensive

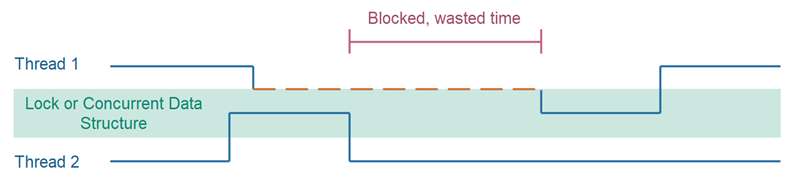

When two threads try to enter a synchronized block in Java at the same time, one of the threads will be blocked, and the other thread will allowed to enter the synchronized block. When the thread that entered the synchronized block exits the block again, a waiting thread will be allowed to enter the block.

Entering a synchronized block is not that expensive - if the thread is allowed access. But if the thread is blocked because another thread is already executing inside the synchronized block - the blocking of the thread is expensive.

Additionally, you do not have any guarantee about exactly when a blocked thread is unblocked when the synchronized block is free again. This is typically up to the OS or execution platform to coordinate the unblocking of blocked threads. Of course it will not take seconds or minutes before a blocked thread is unblocked and allowed to enter, but some amount of time can be wasted for the blocked thread where it could have accessed the shared data structure. This is illustrated here:

Hardware Provided Atomic Compare And Swap Operations

Modern CPUs have built-in support for atomic compare and swap operations. Compare and swap operations can be used in some situations as a replacement for synchronized blocks or other blocking data structures. The CPU guarantees that only one thread can execute a compare-and-swap operation at a time - even across CPU cores. This tutorial contains examples later of how that looks in code.

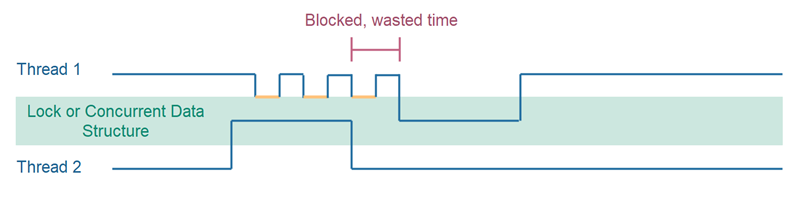

When using a hardware / CPU provided compare-and-swap functionality instead of an OS or execution platform provided synchronization, lock, mutex etc. , the OS or execution platform does not need to handle the blocking and unblocking of threads. This results in shorter amounts of time where a thread waits to execute a compare-and-swap operation, and thus results in less congestions and higher throughput. This is illustrated below:

As you can see, the thread trying to enter the shared data structure is never fully blocked. It keeps trying to execute the compare-and-swap operation until it succeeds, and is allowed to access the shared data structure. This way the delay before the thread can enter the shared data structure is minimized.

Of course, if the thread is waiting in the repeated execution of compare-and-swap for a long time, it may waste a lot of CPU cycles which could instead have been used on other tasks (other threads). In many cases that is not the case, though. It depends on how long the shared data structure remains in use by another thread. In practice, shared data structures are not in use for very long, so the above situation should not occur that often. But again - it depends on the concrete situation, code, data structure, number of threads trying to access the data structure, load on the system etc. In contrast, a blocked thread does not use the CPU at all.

Compare and Swap in Java

Since Java 5 you have access to compare and swap functions at the CPU level via some of the new atomic classes

in the java.util.concurrent.atomic package. These classes are:

- AtomicBoolean

- AtomicInteger

- AtomicLong

- AtomicReference

- AtomicStampedReference

- AtomicIntegerArray

- AtomicLongArray

- AtomicReferenceArray

The advantage of using the compare and swap features that comes with Java 5+ rather than implementing your own is that the compare and swap features built into Java 5+ lets you utilize the underlying compare and swap features of the CPU your application is running on. This makes your compare and swap code faster.

Compare And Swap as Guard

The compare and swap functionality can be used to guard a critical section - thus preventing multiple threads from executing the critical section simultaneously.

Below is an example showing how to implement the lock() method shown earlier using the

AtomicBoolean class using compare and swap functionality that thus works as a guard

(only one thread at a time can exit the lock() method).

public class CompareAndSwapLock {

private AtomicBoolean locked = new AtomicBoolean(false);

public void unlock() {

this.locked.set(false);

}

public void lock() {

while(!this.locked.compareAndSet(false, true)) {

// busy wait - until compareAndSet() succeeds

}

}

}

Notice how the locked variable is no longer a boolean but an AtomicBoolean.

This class has a compareAndSet() function which will compare the value of the AtomicBoolean

instance to an expected value, and if has the expected value, it swaps the value with a new value.

The compareAndSet() method returns true if the value was swapped, and false

if not.

In the example above the compareAndSet() method call compares the value of locked to false

and if it is false it sets the new value of the AtomicBoolean to true.

Since only one thread can be allowed to execute the compareAndSet() method at a time, only one thread

will be able to see the AtomicBoolean with the value false, and thus swap it to true.

Thus, only one thread at a time will be able to exit the while-loop - one thread for each time the

CompareAndSwapLock is unlocked via the unlock() method's call to locked.set(false) .

Compare and Swap as Optimistic Locking Mechanism

It is also possible to use compare and swap functionality as an optimistic locking mechanism. An optimistic locking mechanism allows more than one thread to enter a critical section at a time, but only allows one of the threads to commit its work at the end of the critical section.

Below is an example of a concurrent counter class that uses an optimistic locking strategy:

public class OptimisticLockCounter{

private AtomicLong count = new AtomicLong();

public void inc() {

boolean incSuccessful = false;

while(!incSuccessful) {

long value = this.count.get();

long newValue = value + 1;

incSuccessful = this.count.compareAndSet(value, newValue);

}

}

public long getCount() {

return this.count.get();

}

}

Notice how the inc() method obtains the existing count value from the count variable,

an AtomicLong instance. Then a new value is calculated based on the old value. Finally,

the inc() method attempts to set the new value in the AtomicLong instance via a

call to compareAndSet().

If the AtomicLong still has the same value as when it

was last obtained, the compareAndSet() will succeed. But if another thread has incremented the value

in the AtomicLong in the meantime, the compareAndSet() call will fail, because

the expected value (value) is no longer the value stored inside the AtomicLong.

In that case, the inc() method will take another iteration in the while-loop

and try to increment the AtomicLong value again.

| Tweet | |

Jakob Jenkov | |