Single-threaded Concurrency

- Single-threaded Concurrency is Still New Ground

- Classic Multi-threaded Concurrency

- Single-threaded or Same-threaded Concurrency

- Single-threaded Concurrency Benefits

- Single-threaded Concurrency Challenges

- Single-threaded Concurrency Designs

- Thread Loops

- Agents

- Thread Loops Call Agents

- Agents May Call Other Agents

- Single-threaded Task Switching

- Increment Size Balancing

- Prioritized Execution

- Agent Parking

- Scaling Single-threaded Concurrency

- Event Loops vs. Thread Loops

Jakob Jenkov |

Single-threaded Concurrency means making progress on more than one task at a time from within a single thread. Traditionally you would use multiple threads to make progress on more than one task at a time, with each thread making progress on its own task. Using traditional multithreaded concurrency the switching between different tasks was accomplished by the OS and CPU switching between different threads. However, using single-threaded concurrency techniques, a single thread can in fact make progress on multiple tasks by switching between making progress on each of the tasks. In this single-threaded concurrency tutorial I will explain how single-threaded concurrency works, and what benefits a single-threaded concurrency design gives.

Single-threaded Concurrency is Still New Ground

I started researching single-threaded concurrency designs while looking for a better threading model for single-threaded server designs for use with non-blocking IO using Java NIO. High performance IO toolkits such as Netty, Vert.x and Undertow use a single-threaded server design. Node.JS also uses a single-threaded design. Both Vert.x and Undertow uses Netty underneath (as far as I understand), and are thus all subject to Netty's thread model.

Netty's thread model is centered around a concept called an event loop. An event loop is a thread that runs in a loop - looking for events happening in your system. When an event occurs, your code called so your code can respond to it.

While the event loop thread design works well for some types of systems and workloads, there are other types of systems and workloads where it works less well. Therefore I decided to look elsewhere for single-threaded concurrency designs to match my needs. I will explain all this in more detail later in this single-threaded concurrency tutorial, by the way.

I did not find that much information about single-threaded concurrency designs outside of Netty and Node.JS. Perhaps it is hidden in scientific articles behind a paywall, or something. Or maybe it is just not a heavily researched area.

Since I did not find that much written about single-threaded concurrency designs, I had to come up with some designs myself. I present these designs in this single-threaded concurrency tutorial. However, I suspect it is possible to come up with better designs over time (it would be quite weird if that was not the case). If you have any ideas or references, I would be very interested in learning about them! Find me on some of the social media sites and write me !

Please note: This tutorial is still work in progress. More will be added in a near future!

Classic Multi-threaded Concurrency

In a classic multi-threaded concurrency architecture you will typically assign each task to a separate thread for execution. Each thread only executes a single task at a time. In some designs a new thread will be created for each task, and the thread thus dies once the task is completed. In other designs a pool of threads is kept alive which take one task at a time from a task queue, executes it - and then takes another task etc. See my tutorial about thread pools for more information.

Multi-threaded architectures have the advantage that it is relatively easy to distribute the work load across multiple threads and multiple CPUs. Just give the task to a thread and let the OS / CPU schedule that thread to a CPU.

However, if the tasks being executed need to share data, a multi-threaded architecture can lead to a lot of concurrency problems such as race conditions, deadlock, starvation, slipped conditions, nested monitor lockout etc. In general, the more multiple threads share the same data and data structures, the higher the probability is that a concurrency problem may occur. The more you need to scrutinize your design, in other words.

A classic multi-threaded architecture can also sometimes lead to congestion when multiple threads try to access the same data structure at the same time. Depending on how well a given data structure is implemented some threads may be blocked waiting for access while other threads are accessing the data structure.

Single-threaded or Same-threaded Concurrency

The alternative to a classic multithreaded concurrency architecture is a single-threaded or same-threaded concurrency architecture. In a single-threaded concurrency design you will have to implement task switching yourself.

You can scale a single-threaded architecture up to use multiple threads, where each thread behaves as if it was a separate, isolated single-threaded system. In that case I refer to the architecture as same-threaded. All data needed to execute the task is still kept isolated within a single thread - within the same thread.

Single-threaded Concurrency Benefits

Single-threaded concurrency designs have a few benefits over multithreaded concurrency designs, in my opinion. I will argue what I believe these benefits are here.

Full Thread Visibility

First of all, single-threaded concurrency avoids most of the concurrency problems that can occur with multithreaded concurrency. When the same thread executes multiple tasks you avoid concurrency problems such as thread visibility issues, where updates to a shared data structure not visible to other threads.

Using multithreaded concurrency you will have make sure that you use the right mix of synchronization, volatile variables and / or concurrent data structures to guarantee that updates to a data structure shared by multiple tasks, and thus by multiple threads, are visible to other threads.

See my tutorials about the Java Memory Model and Java Happens Before Guarantee for more information about Java thread visibility problems.

No Race Conditions

When you only have one thread accessing a data structure shared by multiple tasks (because all the tasks are executed by the same thread), you avoid the problems of race conditions. Race conditions can occur when multiple threads access the same critical section without any guaranteed thread access ordering. You can read more about these problems in my tutorial about Race Conditions and Critical Sections.

Control Over Task Switching

When you switch between tasks yourself you control when that switch happens. You can make sure that shared resources are left in a sensible state before switching, and you can decide how big work increments (chunks) it makes sense to execute before switching.

Being able to decide how big a chunk (increment) of work to execute before switching to another task gives you more control over how you utilize the CPU. Small work increments results in more task switching. Larger work increments results in less task switching. Task switching is an overhead you want to minimize. The CPU cycles spent pausing from one task and resuming another is wasted. That CPU time does not by itself produce any useful work for your application. Maybe you don't want tasks under a certain size to be interruptible at all - to avoid unnecessary task switching.

Being able to decide work increment sizes also enables you to prioritize one task over another. If you are switching between two tasks you can decide that one task is allowed to execute only 1 work increment at a time whereas the other task is allowed to execute 2 or more work increments at a time. Thus, the second task will be given more CPU time than the first task. You can control this task prioritization yourself.

Control Over Task Prioritization

It is possible to implement single-threaded task switching in a way so that you can prioritize some tasks over other tasks - meaning giving some tasks more CPU time than others. I will get back to this later in this tutorial.

Single-threaded Concurrency Challenges

Using a single-threaded concurrency design comes with a few challenges too. I will describe some of these challenges below.

It is possible to overcome each of these challenges without losing the simplicity advantage of the single-threaded concurrency architecture, and without overly complicating the overall design too much.

Implementation Required

Having to implement task switching yourself requires that you learn how to implement such designs, as well as actually implement them. This is a challenge. It also adds a bit of overhead to your code base (although not that much I would argue). Luckily, it is possible to create single-threaded task switching designs that can be reused across applications, so you can minimize the implementation overhead.

Blocking Operations Have to be Avoided or Handled in Background Threads

If a task needs to perform a blocking IO operation, then the task and the thread will remain blocked until that IO operation completes. The thread cannot switch to another task while waiting for the blocking IO operation to complete.

Because of this blocking IO operation limitation it can be necessary to execute such tasks in their own background threads - thus reverting to the classical multithreaded design for such tasks.

A Single Thread Can Only Utilize a Single CPU

A single thread can only utilize a single CPU. If your application runs on a computer with more than one CPU or CPU core, and you want to utilize them all, you will have to scale your single-threaded design up to a same-threaded design. This is possible to do, although it requires a bit of work.

Single-threaded Concurrency Designs

Now let's have look at some single-threaded designs providing the functionality I have mentioned earlier, so you can see for yourself how they work, and understand their pros and cons.

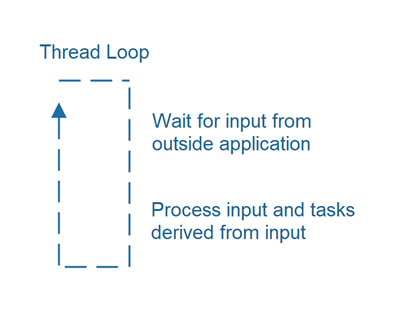

Thread Loops

Most long-running applications execute in some kind of a loop, where the main application thread is waiting for input from outside the application, processes that input, and then goes back to waiting.

This kind of thread loop is both used in server applications (web services, services etc.) and GUI applications. Sometimes this thread loop is hidden from you. Sometimes not.

Pausing the Thread Loop

You might wonder if a thread executing in a tight loop over and over will waste a lot of CPU time. If the thread is running without having any real work to do, then yes, that may waste a lot of CPU time. However, the thread executing the loop is free to "sleep" if it estimates that sleeping a few milliseconds would be okay. That way the CPU time waste can be decreased.

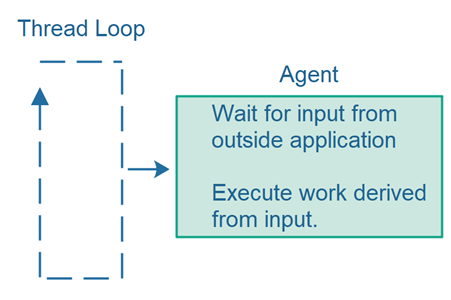

Agents

A thread loop typically calls some component which carries out the work of the application. I refer to this component as an Agent. An agent is a job-like component which carries out work.

The life span of an agent may vary. An agent may:

- Run for the entire life-time of your application.

- Run a longer-running job - which eventually finishes.

- Run a one-off task - which finishes quickly.

Thus, an agent may execute your application's long-running logic, a single but long-running job consisting of many smaller tasks, or a single one-off task that finishes almost immediately. So, the term agent covers multiple sizes of tasks and responsibility.

I prefer the term agent over alternative terms such as job or task, because the life span, responsibilities and abilities of an agent may go beyond what we would normally consider a single job or task. I think of an agent as a component that executes jobs and tasks. It is not itself a job or a task - even though it can look like that in some situations.

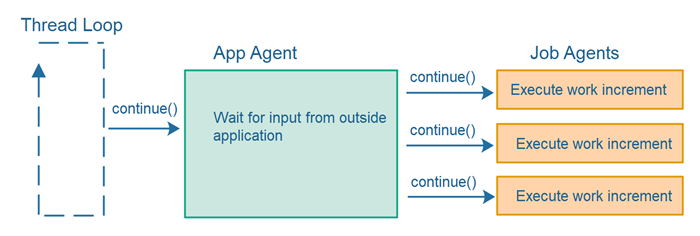

Thread Loops Call Agents

Thread loops typically call an agent component repeatedly - handing over the actual responsibility of the application to the agent. This design splits the responsibility between the thread loop and the agent like this:

The thread loop takes care of looping (repeating the calls to the agent) and detecting when the agent has terminated, and thus terminate the thread loop. The agent is responsible for executing the application logic itself, but not the looping.

Using this design you can create different types of thread loops which can be combined with different kinds of agents. Here is how this design looks:

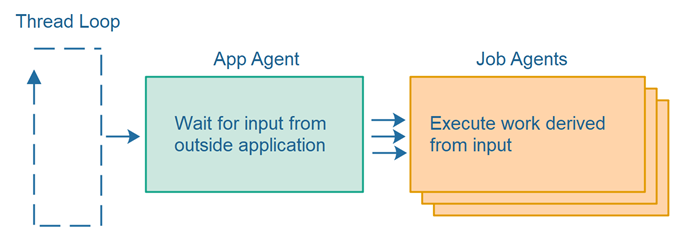

Agents May Call Other Agents

An agent may divide its work among other agents. Thus, agents have different levels of responsibility. Here is a diagram illustrating this division of responsibility among a single app level agent and multiple job level agents:

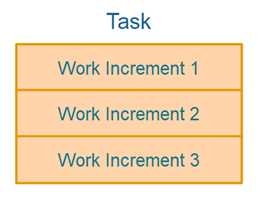

Single-threaded Task Switching

What if some of the jobs executed by the job agents illustrated in the diagram in the previous section take a long time to finish? If the job agent simply executed the complete amount of work when called the first time from the app agent - then the system as a whole (thread loop + agents) would be blocked from making progress on any other jobs or tasks while the first job agent finished the entirety of its work.

To be able to make progress on more than one task seemingly at the same time, the thread making progress on the tasks must be able to switch between the tasks. This is also referred to as task switching. When you only have a single thread available you need to make the task switching possible via your code design.

For task switching to be possible within a single thread, each task must be split up into one or more increments as illustrated below:

Whenever an agent is called it will execute one or more work increments. Sooner or later all work increments will have been executed, and the whole task is finished.

The loop of calling agents over and over again, having them execute a work increment each time, is illustrated here:

Increment Size Balancing

If a single thread is to be able to switch between multiple tasks it is imperative that these tasks are not divided into too big increments. In other words, it is the responsibility of each task to help assure fair division of execution time between the tasks. Exactly what the right size is, depends on the concrete task and your application in general.

Prioritized Execution

It is possible to prioritize execution of some tasks over others. You could implement this by passing a parameter when calling an agent telling the agent how many work increments to execute. Thus, some agents might be instructed to execute only 1 work increment, while others might be instructed to execute 2 or more work increments. This will lead to some tasks getting more CPU execution time than others, and they will thus complete faster.

Agent Parking

If an agent is waiting for some asynchronous operation to finish, e.g. a reply from a remote server, the agent will not be able to make any more progress until the asynchronous operation it is waiting for has finished. In that case it may not make sense to call that agent over and over again just for the agent to immediately realize that it cannot make any progress and return control immediately to the calling thread.

In such situation it may make sense for an agent to be able to "park" itself so it is no longer being called. When the async operation finishes the agent can be unparked and reinserted into the active agents which are called continuously to make progress. Of course, to be able to unpark an agent - some other part of the system must detect that the asynchronous operation has finished and figure out which agent to unpark.

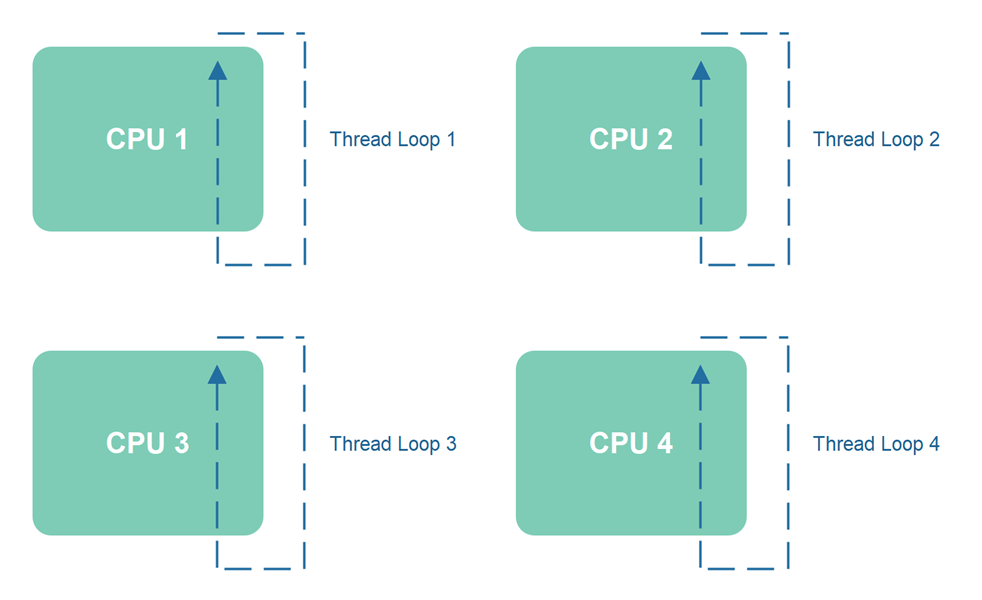

Scaling Single-threaded Concurrency

Obviously, if you only have a single thread executing within your application, you cannot take advantage of more than one CPU. The solution is to start more than one thread. Typically, one thread per CPU - depending on what kind of tasks your threads need to execute. If you have tasks that need to execute blocking IO work, such as reading from the file system or network, then you might need more than one thread per CPU. Each thread will be blocked doing nothing while it waits for the blocking IO operations to finish.

When you scale up a single-threaded architecture to multiple single-threaded subsystems, it is no longer technically single-threaded. However, each single-threaded subsystem will typically be designed as, and behave as, a single-threaded system. I used to refer to such multi-threaded single-threaded systems as same-threaded systems, though I am not sure that is actually the most precise term to use. We might need to revisit these different designs and come up with more descriptive terms for them in the future.

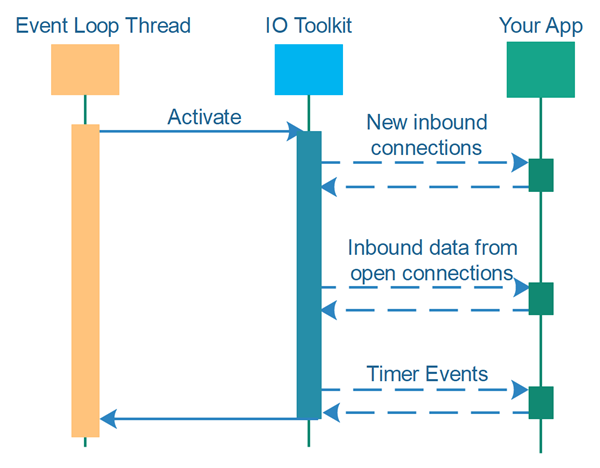

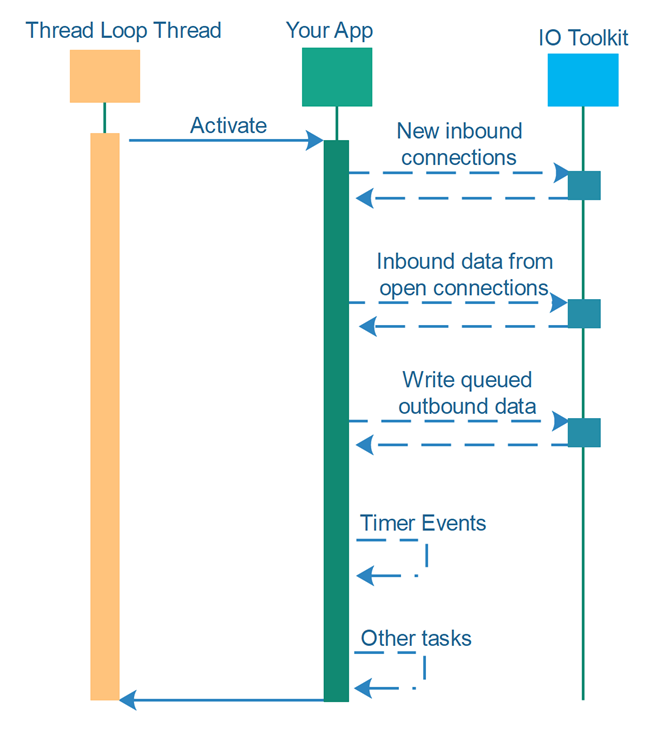

Event Loops vs. Thread Loops

In the beginning of this single-threaded concurrency tutorial I mentioned that the event loops of toolkits such as Netty are different than the thread loops I suggest using in this tutorial. To illustrate the difference I have summarized the control flow of event loop and thread loop design in the following two diagrams.

The first diagram below shows an event loop. The thread executing the event loop first calls the event loop which then calls your application code when various events occur. The time in between the events is controlled by the event loop code. Your application cannot utilize that.

The second diagram below shows a thread loop. The thread executing the thread loop first calls your application which then calls the IO toolkit to check for new inbound connections, or new incoming data on any already open connections, or timer events.

In a thread loop design any time available in between detected events can be used by the application for whatever purposes it desires. For instance, the application could continue make progress on a set of tasks that have not yet finished, using single-threaded task switching.

Additionally, if the application has a lot of work going on, it can choose not to check for new inbound connections, or not to read incoming data from the open connections - implementing backpressure against the network that way. The application can then focus on just executing the tasks that are currently ongoing.

This freedom to choose when to check for events and what to do with time between events is why I prefer the thread loop design over the event loop design. Granted, the design difference is subtle, and it will require somewhat more code from you, but it also gives you greater control and flexibility.

| Tweet | |

Jakob Jenkov | |